When I sit down with a veteran Texas fourth-grade teacher who’s spent two decades in the classroom, she immediately shows me her favorite sweatshirt. Emblazoned across the front are five simple words that encapsulate her teaching philosophy: “You are more than the test.”

Her eyes reflect both concern and determination as she describes the anxiety epidemic she witnesses each year around standardized testing time.

“Every year I’ve taught, I’ve had to get an administrator to come in and take a kid out because they’re openly weeping at their chair,” she tells me, shaking her head. “These are even kids I know are very capable of being successful.”

The Emotional Toll of High-Stakes Testing

When I ask what testing season looks like in her classroom, her response is immediate.

“We truly have kids that fall apart the weeks before STAAR, the day of STAAR,” she explains, referencing Texas’s standardized assessment. “You’re talking about nine and ten-year-old kids that don’t have fully developed frontal lobes. Their ability to make decisions in the moment is not similar to an adult’s at all.”

She describes watching bright, capable students crumble under pressure, convinced their entire future balances on a single day’s performance.

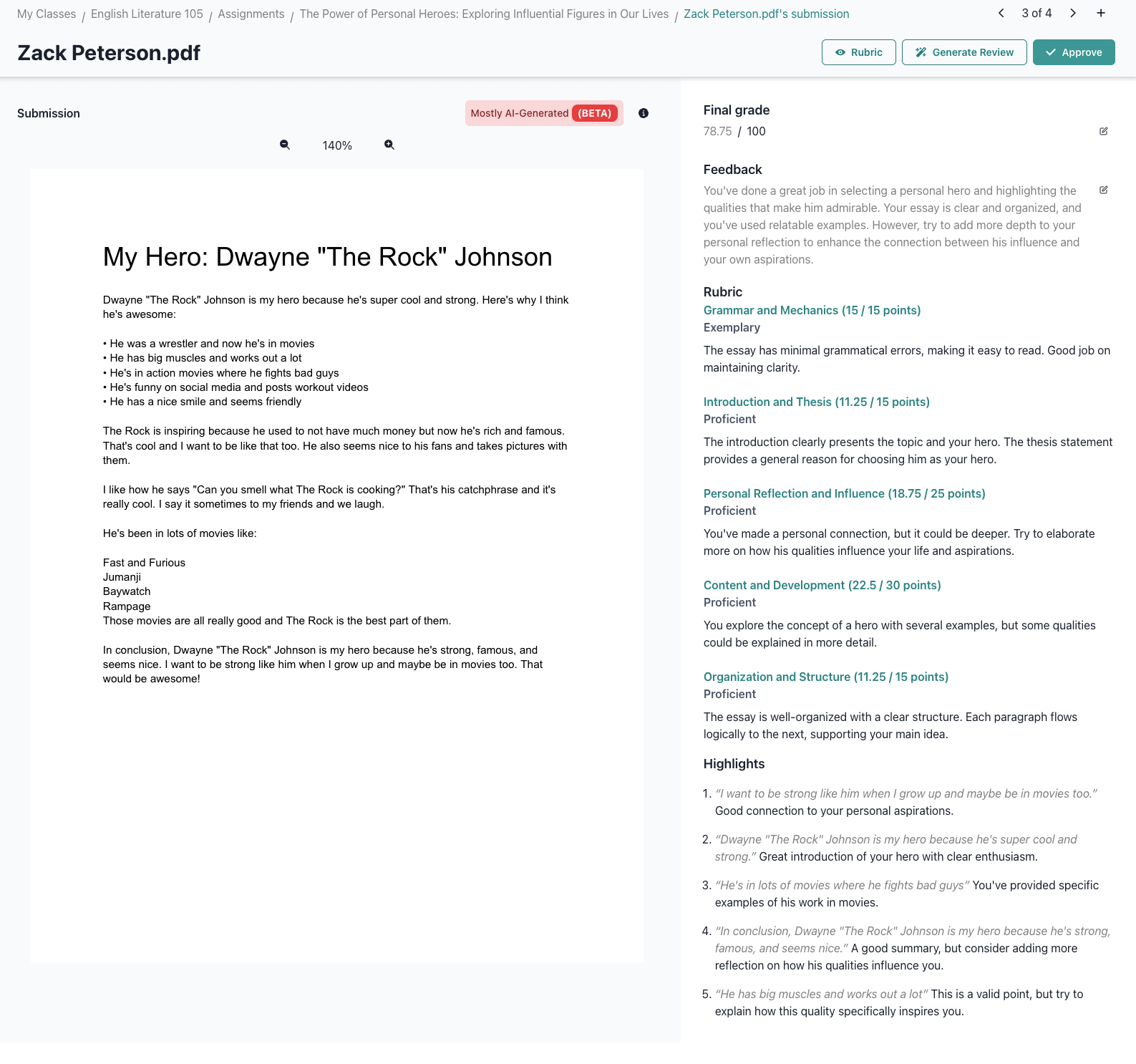

A Different Approach to Test Anxiety

“What do you tell students who are anxious about testing?” I ask.

She leans forward, speaking with the certainty that comes from years of experience. “I tell them every day, ‘You are more than the test.’ If you are doing your very best and I see you applying yourself and growing, I don’t care what the score is.”

This isn’t just empty reassurance. Her classroom operates on a growth mindset philosophy where improvement matters more than perfection.

“So how do you balance maintaining high standards while reducing anxiety?” I inquire.

“I support our school’s expectations,” she explains, referencing what she calls the “30-60-90 rule” (aiming for 90% of students approaching grade level, 60% meeting standards, and 30% mastering content). “I don’t have a problem with that because I think that’s setting high standards in your classroom. We don’t want to lower the bar.”

The difference, she clarifies, is separating performance expectations from a child’s self-worth.

Creating a Supportive Testing Environment

When I ask about practical strategies, she outlines several approaches:

“I want them to know STAAR is a day in the life of fourth grade and there are 364 other days that make you fantastic,” she says.

She builds confidence through varied writing opportunities beyond test preparation, allowing for creativity and personal expression.

“We do a lot of opinion writing,” she explains. “It might kind of seem like it is response to reading, but we’ll read a novel unit and then have them respond: ‘If you were this character, what would you have done?’ So it’s not based just on comprehension… they get to step into the place of the character and completely change the ending or how they would have tackled a problem.”

The Factors Beyond a Teacher’s Control

Our conversation turns to the challenges educators face with standardized testing.

“I have zero control over a kid having a huge fight with their parents before they come into school,” she says frankly. “My students sometimes comes to school without having eaten dinner the night before or breakfast the morning of. I have no control over that, so I try to provide snacks because a hungry kid doesn’t function well.”

She questions the fairness of holding teachers accountable for test scores given these variables: “There are a lot of extenuating circumstances in teaching.”

A Message for All Educators

As our interview concludes, I ask what message she would share with other teachers facing similar testing pressures.

“At the end of the day, honestly, the tests students take throughout their education don’t mean anything compared to who they become as people,” she reflects.

“I want my kids to know the test doesn’t tell me who they are as a person. They’re great people. That test doesn’t define them.”

After twenty years in education, perhaps that’s the most valuable lesson she offers: in a system increasingly focused on metrics and scores, we must remember we’re teaching children, not test results.